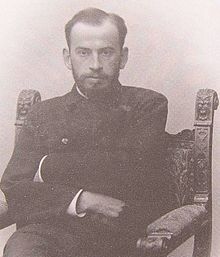

You know that thing where you read something, love it, plan to write a piece on it, but then you watch a movie, read something else …time goes by? And in the meantime, you’ve also discovered walking long distance; taken up boot making; or you took that train trip and now you want to write poems about what you saw from the moving window. But by now you’re making plans to write that short course; you’ve started a new game; or fallen in love; and you’ve taken up French again, as recently as last week, and today is the day you’ll actually read all those tabs you’ve had open since Sunday! If like me you get that hopeless feeling you’re too unfocused to be a real artist, maybe also like me you’ll feel inspired by the writer who is the focus of this month’s Literary Punk podcast: the 19th Century master of the psychological novel, Tolstoy.

‘December 15: attends performance of Mozart’s Don Giovanni. […] Mixed relations with Turgenev; close to Botkin, Reads Balzac, Tocqueville (L’Ancien Régime), Goethe, and Don Quixote. […] March 25: witnesses a guillotining in Paris. July 12 – 20: loses heavily at roulette in Baden-Baden. July 24: on way home sees and admires Raphael’s painting of the Madonna in Dresden. […] 1858 March: reads Gospels, starts unfinished story […] begins passionate affair with married peasant ‘. Tolstoy’s diary entries, in The Cambridge Companion to Anna Karenina, Edited by Donna Tussing Orwin, CUP, 2002, p6.

‘December 15: attends performance of Mozart’s Don Giovanni. […] Mixed relations with Turgenev; close to Botkin, Reads Balzac, Tocqueville (L’Ancien Régime), Goethe, and Don Quixote. […] March 25: witnesses a guillotining in Paris. July 12 – 20: loses heavily at roulette in Baden-Baden. July 24: on way home sees and admires Raphael’s painting of the Madonna in Dresden. […] 1858 March: reads Gospels, starts unfinished story […] begins passionate affair with married peasant ‘. Tolstoy’s diary entries, in The Cambridge Companion to Anna Karenina, Edited by Donna Tussing Orwin, CUP, 2002, p6.

This very big writer’s life didn’t seem to do his art any harm. If you read his diary entries alongside the incredible bibliography he pursued, such as the one presented in the ‘Chronology’ of the excellent volume cited above, Tolstoy’s life reads like his novel! And his novel reads to us of him.

The miracle of Anna Karenina (1878) is that all of Tolstoy’s multitudinous living and reading comes together onto these pages, seamlessly. From that big messy life emerges this novel, “Flawless art” in the opinion of Nabokov; a “masterpiece” if you’re Dostoyevsky (whom, by the way, T “loved”). Tolstoy scholar Barbara Lönnqvist locates the seamlessness of Anna Karenina’s buttery prose with her precise comment: “The character’s integrity and independence and the author’s view of the person are welded together so that no seams are noticeable” (2002, p80).

“I have noticed that any story makes an impression only when one cannot make out with whom the author sympathises.” Tolstoy, 1867 (2002, p80).

For the latest episode of Literary Punk, my guest in the Hookturn studio for a very Russian style conversation that includes everything – laughter, tears, joy, years, books, sex, love and death – is the delightful writer, editor and Feminist commentator, creator and host of Cherchez la Femme and director of Girls On Film Festival, Tavarisha Karen Pickering. We talk about how it’s impossible to side with anyone in this tale of adultery and family. KP: “There are no villains in this story.”

‘1857 April – May: idyllic two months in Switzerland: “I am gasping from love, both physical and ideal. […] I am taking a very great interest in myself. And I even love myself for the fact that there is so much love of others in me” (d, May 12).’ Tolstoy’s diary, in The Cambridge Companion to Anna Karenina, Edited by Donna Tussing Orwin, CUP, 2002, p6.

Tolstoy is Anna, full of love! And of course he is Levin. More interestingly, Tolstoy is a rhythm between the two unforgettable characters of the novel, Anna and Levin, and the unspoken (non-Symbolic) or marginal relation between them and their interleaved stories. How curious, that the driving and memorable ‘love affair’ of the book is not the lovers, Anna and her Vronsky, but the crossed ‘boundary’ between Anna and her Levin, and the coming undone that goes on there. Randomly arranged dialogues if you like, located in each other: passionate love alongside passionate intellect; emancipation then belonging; diversity beside unity. Sex and death. Desire and Realism. Difference and inclusion. Karen commenting so beautifully in the podcast said, “Tolstoy is at the edge of his boundaries.” Philosopher Isaiah Berlin put it this way, Tolstoy longed for unity but celebrated diversity (1953).

Indeed, Tolstoy is all things, and the expression of in-between things, such as those that exist outside the spaces between the chapters, the unrepresentable because deeply unconscious things – the Lacanian Real at the edges of the Realism, if you like. Flaubert said of Tolstoy, “What an artist, and what a psychologist!” Tolstoy’s psychological novel naturally prefigured the psychoanalytical theories of Freud, and his work also carries the extant energy of another new medium for his time: that of the media, a new and radical movement of ideas out to the multitudes.

You could understand someone who hadn’t read him for questioning the punkness of his book, and its inclusion in this podcast series. Considering the trajectory of the novel, it’d be easy to refute Anna’s story, her infamous ending. But it’s an ending which is not the end, and that discursive last chapter is political! Too much so for its day: the journal editor Katkov, who published all previous instalments of the serialised novel, refused to print the finale.

Its writer was most proud to call himself – along with Lermontov – a member of the non-literati. Tolstoy was a radical and censored voice within the Russia of the Tsars. His writing was banned, seized at the presses. And one of his most radical contributions to literature was his imagination for sharing it around:

“I would very much like to put together a cycle of reading, that is a series of books and selections from them which would all speak of that one thing most needful to a person, namely, what life and the good are for him” Tolstoy (2002, p25).

For this reason I nominate the very radical Count, Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy, as a patron honorary of Literary Punk. For his socialist ideals about sharing around the profound human potential of Literature, and for his ecocritical understanding of the cultivation of joy:

‘1894 June 14: “As I was approaching Ovsiannikovo, I looked at the lovely sunset. A shaft of light in the piled up clouds, and there, like a red irregular coal, the sun. All of this above the forest, the rye. Joyful. And I thought to myself: No, this world is not a joke, not a vale of ordeal only and a passage to a better, eternal world, but one of the eternal worlds, which is good, joyful, and which we not only can, but must make finer and more joyful for those living with us, and for those who will live in it after us” (d). Tolstoy (2002, p32).’

To the beauty of coming undone: Joyful!

Anna Karenina, Leo Tolstoy, (1878), Translated by Rosemary Edmonds, Penguin, 1954.

The Cambridge Companion to Anna Karenina, Edited by Donna Tussing Orwin, CUP, 2002.

The Hedgehog and The Fox: An Essay on Tolstoy’s View of History, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, Isaiah Berlin, 1953.

Image: Tolstoy, en.wikisource.org